The Twibill, the English World's Besaigue

Primary tabs

I recently read (and reviewed) Maurice Pommier's children's bookabout woodworking called GrandPa's Workshop. It's a charming book and it introduced me to the uniquely French tool called the besaigue. To a modern American woodworker's eyes, it's an odd, ungainly looking tool, but after hearing how it might be used, I've come to see how it could actually be useful in the right situation. A besaigue, pronounced as best as I can determine as Bay-say-gwe', is a long, double-tipped chisel, with a mortising chisel on one end, and a broad, flat chisel or firmer chisel on the other end. In the middle is a long rod with a handle attached at the midpoint. The purpose of the tool is for timber framing. The long end not being used is placed on the shoulder, and the handle is used to pare down or punch down into a beam to create a mortise. From other reading, it seems to have been commonly used up until perhaps the 17th century along with a large brace and bit to create round-ended mortise slots for structural timbers.

French Style besaïgue from the collection of the Ethnographic Museum of Geneva

French Style besaïgue from the collection of the Ethnographic Museum of Geneva

What I didn't learn from this reading, however, is whether or how this tool was ever used in the English-speaking world.

What I didn't learn from this reading, however, is whether or how this tool was ever used in the English-speaking world.

Granted, it's a tool whose use has largely faded into dimly remembered history, even in France, but I did wonder while reading the story if there was anything like it in England, or elsewhere in Europe.

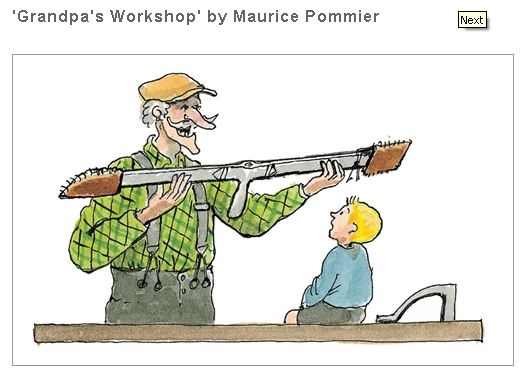

Well, I was recently watching a Youtube video about English timber framing when I came across a section that answered that very question. it's a video that was made by the East Sussex Archaeology and Museum Partnership and it's called "Early medieval timber work". You can find the video here. Youtube video # aI8VWjpKBlA. Most of this recording describes how to square a log to make a beam, using traditional tools, namely axes. There's nothing on location that matches the description of a besaigue, or anything similar. But at 2 minutes and 26 seconds in, the journalist asks the head worker a very important question, "How do you know that they did it this way?" The gentleman very helpfully responds that there are two types of evidence for what we know about pre-industrial timber framing, tool marks on the surviving beams, and pictures in old manuscripts. At about the 2:40 mark, he points to a block cut illustration showing a fellow using an axe to square a log. But more interestingly is what is happening in the background. (He even points out the background work.)

Now at this point I originally misheard him. He said something about how we can see another worker using a 'twinbill' or 'twibyl', or something that sounded like that. But the picture looks a heck of a lot like the illustrations I've recently seen of a besaigue . . . granted, with a longer handle. This mishearing . . . I thought he said 'twinbill' originally, led me down a fairly deep rat-hole. I could find no references to a tool called a twinbill anywhere easy to research. It did, however, bring up the common baseball term of the twinbill . . . which raises another issue which I'll discuss below.

Now at this point I originally misheard him. He said something about how we can see another worker using a 'twinbill' or 'twibyl', or something that sounded like that. But the picture looks a heck of a lot like the illustrations I've recently seen of a besaigue . . . granted, with a longer handle. This mishearing . . . I thought he said 'twinbill' originally, led me down a fairly deep rat-hole. I could find no references to a tool called a twinbill anywhere easy to research. It did, however, bring up the common baseball term of the twinbill . . . which raises another issue which I'll discuss below.

But after reviewing the video several times, it seemed to me that he was actually saying 'twibill', rhyming with "dry hill". There's probably somebody reading this that is well aware of this tool, but I had never heard of anything by this name. Searching for 'twibill', as opposed to my results for 'twinbill', resulted in a wealth of information. It's someimes called a 'twybill'. The twibill is defined in the Wiktionary as a double ended axe, or a mattock, or the third definition . . .

But after reviewing the video several times, it seemed to me that he was actually saying 'twibill', rhyming with "dry hill". There's probably somebody reading this that is well aware of this tool, but I had never heard of anything by this name. Searching for 'twibill', as opposed to my results for 'twinbill', resulted in a wealth of information. It's someimes called a 'twybill'. The twibill is defined in the Wiktionary as a double ended axe, or a mattock, or the third definition . . . A double bladed tool used in gate type hurdle making for cutting out mortices, with a flat chisel and a mortice chisel or hook, similar to the much larger french carpenter's tool, the bisaigue (or besaigue)

. THERE we are, Mr. Besaigue!

I have no idea what manuscript this illustration comes from. If anyone knows, please let me know. I can't make it out in the video, although it is possible to pick out the source of the other manuscript they mentioned, the one showing the planking of the beam using a two person saw.

However, many of the modern descriptions and pictures seems to display what are clearly battle axes, or mattocks, and only as a final aside mention that 'the implement may also be used for carpentry work in some cases.' Most of the modern references don't describe it as a distinctly and deliberately carpentry joinery tool as the term is used by the East Sussex museum fellow. Now, I've encountered a mattock. I even used one on my father's farm. We used it to dig holes in packed clay to install fence posts. The timber framing tool, whatever you call it, is clearly a much different creature. The illustration shown by the timber framing re-enactors clearly shows a twibill that is longer, straighter, and thinner than a mattock. And if you look at just the head, it looks almost identical in dimensions to the French besaigue. (Twibills are often describes as being curved, much shorter versions of the French tool.) In this illustration, if you took the wooden handle off, (i.e. so that it is no longer a 'pole-axe' shape) then you end up with something that is just a slightly curved besaigue.

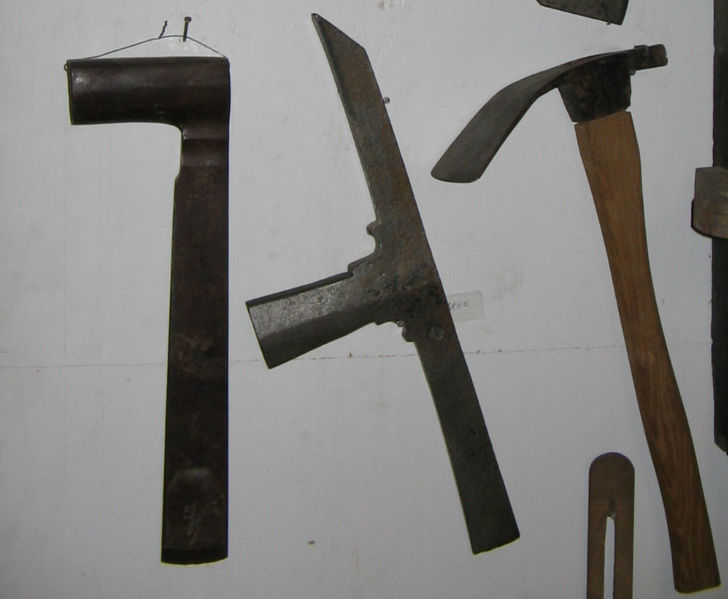

There is one picture that lists a twibill on Wikipedia, taken in Denmark I believe. This shows three tools, from left to right: a 'slick axe', a twibill in the middle, and an adze on the right. Photo by B. M. Askholm, www.baskholm.dk/baskholm. That middle tool certainly looks like the tools described as being 'twibills'. I wonder if the illustration shows a French scene? Or perhaps the longer stylle twibill was actually in use during the period, but none of the longer, thinner forms didn't survive to modern times. In either case, we see a simlar form: two chisels attached back to back with a handle in the middle, with one chisel being a mortise chisel and the other an almost axe-shape firmer chisel. The besaigue illustrations show a much lighter connection between the handle and the head, indicating that it was probably never meant to be swung using a long handle. The twibill at left, however, has a much heaftier connection, so this tool probably would have had a pole handle. But also clear is that this is no mattock.

There is one picture that lists a twibill on Wikipedia, taken in Denmark I believe. This shows three tools, from left to right: a 'slick axe', a twibill in the middle, and an adze on the right. Photo by B. M. Askholm, www.baskholm.dk/baskholm. That middle tool certainly looks like the tools described as being 'twibills'. I wonder if the illustration shows a French scene? Or perhaps the longer stylle twibill was actually in use during the period, but none of the longer, thinner forms didn't survive to modern times. In either case, we see a simlar form: two chisels attached back to back with a handle in the middle, with one chisel being a mortise chisel and the other an almost axe-shape firmer chisel. The besaigue illustrations show a much lighter connection between the handle and the head, indicating that it was probably never meant to be swung using a long handle. The twibill at left, however, has a much heaftier connection, so this tool probably would have had a pole handle. But also clear is that this is no mattock.

| Bills and Baseball |

I have very little to support the argument that there's any relationship between the besaigue, the twibill, and the twin bill we know about today in the U.S. However, I do have an idea. What is a twin bill? The only real usage we have is to describe two events that occur on the same day for one price, such as two baseball games or two plays. For as long as I can recall, I had assumed that this term, twin bill, was a reference to the meaning of bill related to a posted document. The Etymology Dictionary describes this other kind of bill as coming from ""written statement," mid-14c., from Anglo-French bille, Anglo-Latin billa "list," from Medieval Latin bulla "decree, seal, sealed document". LIke a bill passing through congress. Or a Bill of Lading. So a twin bill must refer to two events that were posted up on a bulletin board or some public place on a single sheet of paper. Right? Sort of like a hand bill. But maybe not. Maybe there was some memory in the mid 19th century of the twin headed tools that had been around in the past when the sport of baseball was coming into being. After all, most of the players came from working class stock. What is a twibill? A tool with two heads . . . a doubleheader. How does that relate to a piece of paper? I doubt they posted the pictures of both pitchers on those early twin bill announcements, although that is one other option. Or perhaps they were being metaphorical and decided that a Baseball Mattock was just too silly sounding. - jo |

So . . twibill, or twin billed tool. This terminology, and its etymology, are very interesting to me. I had been under the assumption that the bill was because the head of an axe looks a bit like a duck's bill, so the tool was named after the animal. But it turns out to be the other way around. A 'bill' is an old (OLD) word for an axehead. The ancient Swedes' (or Norse) word for a hatchet was a 'bill'. The Saxons in England clearly brought the word along. The duck's bill is named for the axe, not the other way around. (Check out the Online Etymology Dictionary entry for 'bill'.) So the 'twin bill' literally is a twin hatchet, probably a much older form than most of the other tools we've mentioned here. (Except, perhaps, for the Adze, which seems to be a really old shape, often depicted in the art of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.)

This history of a bill as amilitary weapon gives added insight to the way that the Grandfather in Mr. Pommier's story talks about the besaigue as "the carpenter's sword." Whether or not twibill was ever used to describe a similar tool in the New World is another question. I have a suspicion that there were at least some old memories here, of the twibill or of something similar.It wouldn't surprise me if the toolboxes of the Pilgrims or the St. Augustine settlers didn't include a double-headed carpentry tool or two. (See sidebar "Bills and Baseball")